Nothing seems to stir up more disagreements among writers these days than all the issues related to pricing books. Unlike in traditional publishing, writers have lots of control about how they market their books on the indie side. And while there is no one-size-fits-all approach to pricing or marketing, it’s become pretty clear to me that few writers understand how powerful (and nuanced) a marketing tool FREE! can be in a digital marketplace where the cost of production and distribution, at least for the indie writer, is nearly zero. If a dairy farm wants to give away free cheese samples, they have to produce the cheese, transport it to the grocery store, and pay someone to hand out the samples. If a writer wants to make an ebook for free, all it takes is a few clicks of a button.

But there are caveats. Lots of caveats.

But there are caveats. Lots of caveats.

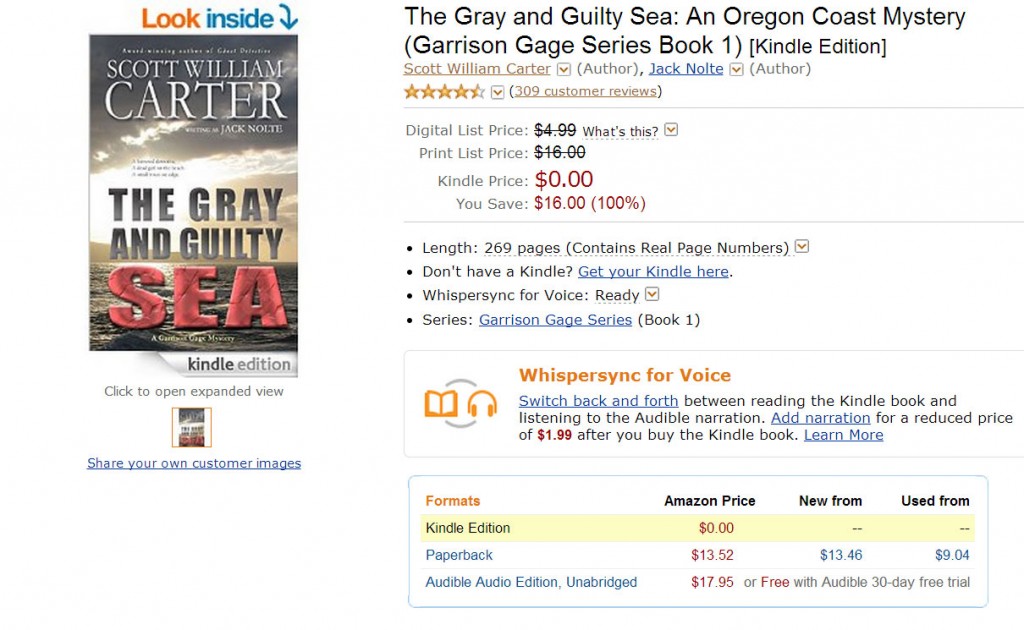

In the month of August, I gave away 150,000 ebooks of The Gray and Guilty Sea. Sales of the two sequels exploded. My mailing list doubled overnight. Hundreds of positive reviews poured in (on Amazon alone, the number of reviews on The Gray and Guilty Sea jumped from 30 to over 300 in a few weeks) and I’ve gotten dozens of nice emails from readers. It’s the most effective promotion I’ve ever done. More importantly, I did it not because I was desperate, but because I believed in my work. I believed that if readers got to spend a few hours with the curmudgeonly Garrison Gage, a lot of them would want to spend a few hours more and would be willing to pay money to do so.

For the most part, this post is not about the mechanics of making ebooks free. Lots of other writers have written about the how, so there is no need for me to reiterate it here. (Here’s one post to get you started.) What I want to write about is why making something free is sometimes (but not always) the smartest thing a writer can do.

Dan Ariley, the noted professor of psychology and behavioral economics at Duke University, writes in Predictably Irrational about the an experiment they performed that clearly shows the irrational draw of free things. I highly recommend reading his whole book, but here’s an except from his blog that sums up this experiment:

I developed an appreciation for the surprising power of FREE! from the experiments my colleagues and I conducted on how people respond to things when their cost is zero (included in Predictably Irrational). For instance, when we set up a temporary candy stand and sold mouthwatering Lindt truffles (which usually cost around 50 cents) for 15 cents and ho-hum Hershey Kisses for 1 cent, 73% of the chocolate-lovers who stopped by made the rational decision and chose the superior and highly discounted Lindt truffles. But when we lowered the price by 1 cent for each item—resulting in a cost of 14 cents and 0 cents respectively—suddenly demand reversed and 69% of consumers chose the free Kisses.

He performed a similar experiment with Amazon gift certificates where people choose a $10 certificate for free over a $7 gift certificate that was worth $20. No other discounts produced the same effect. The takeaway is that our hoarding response to FREE! is an evolutionary trait, a survival instinct that helped us persevere in a world of scarce resources. By making something of value free, it triggers this hoarding instinct. We choose free items even over something cheap of clearly higher value. That’s how powerful it is. Now, to tie Ariley’s experiment into books, imagine if the truffles had been free, not the Hershey kisses, just one per customer. And if you liked the truffles, you could buy a bag of truffles at a very reasonable price right there at the table.

The key to giving away free books is to give away a Lindt truffle and not a Hershey kiss, and to do it in a way that the buyer can easily buy more once they have tried the sample. If your book has a presentation that makes it look like a truffle (by blurb, cover, original price, and of course the contents), it’s going to look very attractive next to a bunch of Hershey kisses (books with bad covers and blurbs and, more often than not, contents). When a writer gives away the first book in a series away for free, it’s like having the bag of truffles right there at the table. It’s also why it’s imperative that the book must be given away within the book retail ecosystem and not outside of it (like on an author’s website). Take a look at this screen shot from the Amazon page for The Gray and Guilty Sea:

It looks very much the same at BN.com, iTunes, and other retailers. That $4.99 with the line through it is critical in establishing that this is a truffle and not a kiss. The sequels priced at $4.99 and $5.99 also help reinforce the impression that The Gray and Guilty Sea has value. (My pricing strategy for these books is to be just on the low side compared to traditionally published books in my genre. There is also a fair amount of research that indicates, at least for now, that this is the price range that yields the most income.) The reason this is so important is because of the other prominent effect that free has: numerous studies have shown that making something free does make the consumer perceive it as being worth less. That’s why you need lots of countervailing effects that keep reinforcing that the loss leader is worth money; it just happens to be free for the moment. Another great book on the power and pitfalls of free is Chris Andersen’s book Free: The Future of a Radical Price. After first writing about how free snacks at Google conferences are often highly wasted, he addresses this conundrum directly:

People often don’t care as much about things they don’t pay for, and as a result they don’t think as much about how they consume them, free can encourage gluttony, hoarding, thoughtless consumption, waste, guilt, and greed. We take stuff because it’s there, not necessarily because we want it. Charging a price, even a very low price, can encourage much more responsible behavior. The authors of the Penny Closer blog tell the story of a friend who volunteers for a charity that provides people who are down on their luck with transportation—free bus tickets, to be exact. Unfortunately, these tickets, which cost the charity $30 each, are frequently lost. So the charity instituted a new rule—all tickets would cost $1 to help offset the costs of replacement. Suddenly, people lost fewer tickets. Just the act of paying $1 changed how people viewed the ticket. Since they had invested in it, clients seemed to be more careful not to lose it. Even though it was inherently worth something before they had to spend $1 on it, the ticket was somehow worth even more now. The flip side of both these stories is that the imposition of a price, no matter how low, typically decreases participation, often radically. In the Google case, people would take far fewer snacks if they had to pay. In the case of the charity, it distributed far fewer bus tickets. That is the trade-off of Free: Free is the best way to maximize the reach of some product or service, but if that’s not what you’re ultimately trying to do (Google is not trying to maximize snack food consumption), it can have counterproductive effects. Like every powerful tool, free must be used carefully lest it cause more harm than good.

Get that? Free is the best way to maximize reach, but there are downsides, too. It’s not enough to give someone a free book. It must be a free book that both gives them a satisfactory reading experience and leaves them wanting more. In my opinion, readers come back for another book from a writer because a) they are hooked on the author’s voice, b) they want to know what happens next, or c) both. The first is much harder to do. The second isn’t easy either, but it is easier. Hook a reader on an ongoing series character or an ongoing series story arc and they will be very likely to buy the next book. Offering readers a free book or short story that’s not connected to any other books is a bit like offering the consumer a free truffle but then asking them to buy a bag of M&Ms. If they sampled the truffle, they want to buy truffles. For example, I gave away thousands of very short stories on the various e-retailer sites for a couple of years (I couldn’t quite bring myself to charge 99 cents for a five-minute reading experience) before clearly seeing that it had very little effect on sales of my other titles, so I stopped. (A short story prequel tied to a novel does have a positive, effect, however; just not nearly as big an effect as a free novel.)

Now, I want to close this post by addressing a few persistent myths when it comes to free.

1. Giving away books for free devalues them.

No, it doesn’t, not if some the of the conditions I talked about above are met. And, um, ever heard of libraries? More importantly, at least as far as I’m concerned, the book that has the least amount of value is the book that is not read.

2. I made the first book in my series for free and hardly anybody downloaded it.

Assuming you have a good book with a great cover in a popular genre (which is, honestly, 99% of what will determine your success, which means that 99% of the writers reading this will skip right over this sentence), then the biggest reason is that you probably didn’t promote it. It’s not enough to make something free. Nobody’s going to try your free truffle if you set up shop in your garage. The idea is to get people downloading your book who wouldn’t do it otherwise. Again, I don’t want to get bogged down with a lot of mechanics when an hour with Google will teach writers all they need to know, but you must push the free book. Two years ago was different because the early ebook adopters were hoarding free books with very little encouragement. Today is different. For some more thoughts on this, check out Nick Stephenson’s recent posts.

3. Scott, you obviously wrote great books. That’s why it worked and not because of this silly free thing.

It’s true that no amount of marketing can make someone buy something that they don’t want. But there is just no question that this loss leader promotion (what a lot of people call the “permafree” strategy, a term I don’t like very much because I don’t believe in leaving anything free forever) gave my books a shot at a wider audience. That’s all you’re asking for. A shot. My history with the Garrison Gage books is complicated, as some of you know (I talk about it a bit in this post), so I don’t think I was even optimally positioned with these books. I’ve had to put the books through additional rounds of copy editing and improve their covers because of my backwards approach to them. If it worked for me in spite of this, it can clearly work for others. And it has: Russell Blake, Nick Stephenson, Elle Casey, the list goes on and on . . . For more thoughts on how to give yourself a shot as a writer, read David Gaughran’s excellent post, “Starting From Zero.”

4. If 150,000 people downloaded your book, that means a huge percentage of them either didn’t read it or like it. What’s the point in getting your book downloaded if most people don’t read it?

This is the silliest thing to worry about of all, and the most common myth. By the best estimates I can find, J.K. Rowling has sold maybe 70 million copies of the last book of her Harry Potter series. The world’s population is 7 billion. That means even the bestselling writer working today has only reached 1% of the planet with her books. All the people who downloaded my book but don’t end up reading it are not my fans anyway. Whether they have my book on their e-reader or not is immaterial. The ratio of people who try out my first book versus those who go on and buy the sequels does not matter. All that matters is that the total number of people who are going on to buy my other books is growing. If it takes 1,000,000 people downloading my books for free to get me 10,000 true fans that will buy all the books I write, I’ll take that trade off. (That’s one percent, by the way . . .) In many ways, I think the best indicator of my overall success is not my sales, but my growing mailing list.

Last, I just want to say I did very clearly hit the upper end of what this kind of promotion can do. I can’t guarantee similar results for someone else. But what I can say is that this is a proven sales technique that is built on timeless marketing principles. What’s changed in the ebook era is the cost of doing it has dropped nearly to zero and the reach has increased dramatically. Traditional publishers use it, too. In fact, it’s so established that most readers now intuitively grasp why the first book in a series is for free, which makes it work even better. I wasn’t going to write this post at all because it’s fairly well-tread ground at this point, but I have been amazed at how much misinformation and how many myths still persist about free in spite of the evidence. I also heard some chatter that this technique may have worked a few years ago, when ebooks were new, but it’s not working any longer.

Yes, FREE! is complicated. Yes, FREE! doesn’t always work, and sometimes it can even do more harm than good. It’s not like any other kind of discount. But if the month of August is any indication, it clearly still worked for one writer. And it can work for others.

————-

I wrote this blog post for free, taking time away from my fiction to do it. I rarely write these kinds of posts any more, posts aimed more at writers than readers, so I do it as a way of paying it forward. If you want to show your appreciation, please consider linking to this post on Facebook, Twitter, or a blog – or, better yet, spreading the word about my book, The Gray and Guilty Sea, which is also free. I’d love it if a million people downloaded it.

I really believe in the power of free, if used wisely. Can you tell?