Well, that title is a mouthful, isn’t it? I thought of naming this post something shorter and pithier, but as long as that title is, I think it really encompasses what I want to say. And somehow Things Are Going to Be Different Now, while just as accurate, didn’t quite cut it.

The pin oaks and maples outside my office window are alive with crimson and gold, my driveway is littered with leaves that crinkle under my shoes, and the morning air has a bit more bite, so fall must be here. It’s a reminder that change is inevitable. Seasons come, seasons go. Along those lines , it’s my belief that a particular season of publishing is coming to a close: the season of the Early Adopter eBook Bounce.

The pin oaks and maples outside my office window are alive with crimson and gold, my driveway is littered with leaves that crinkle under my shoes, and the morning air has a bit more bite, so fall must be here. It’s a reminder that change is inevitable. Seasons come, seasons go. Along those lines , it’s my belief that a particular season of publishing is coming to a close: the season of the Early Adopter eBook Bounce.

I hesitated about even writing this post, because it may come across more negative than it really is, and I’m sure some people will take it that way. But I’ve been accused of being too Pollyannaish about the indie publishing movement in the past, so perhaps it’s my due to balance things out a bit. And yet, if you read all the way to the end, you’ll see that my overall message really hasn’t changed all that much.

I think the easiest way to go at this is to take my rather long title and break it down one section at a time.

A Tsunami of Wonderful…

Three or four years ago, when the eBook revolution was really beginning to take off (a lot of people point to the holiday season of 2010 as the tipping point), and any objective observer with any sense at all could see that things really were going to be different going forward, there was a fairly prevalent feeling among the literati — the name often given to those esteemed gatekeepers in traditional publishing who see it as their solemn duty to keep out the riff raff — that since anyone could publish a book, anyone would publish a book, and eventually there would be so many bad books that it would make it impossible for the good books to find an audience. One writer, who shall remain nameless, dubbed this effect the Tsunami of Crap. With more and more books bought via ecommerce (most estimates put ebooks+print bought online now at about 50% of the market share and growing), the Tsunami of Crap would eventually overwhelm the system and drown out all the good stuff with the bad.

I never believed it. It’s true that there are more books available to readers than ever before, a massive increase in the past five years. It’s also true that there’s a huge amount of crap out there, crap that can be bought just as easily with your Kindle, Nook, or Kobo device as Jonathan Franzen’s latest or Alice Munro’s or anyone else the literati might deem acceptable. But anyone who understands how online book buying really works should know that there’s no chance that the bad books will ever crowd out the good. You could have thousands of bad books available online or billions, it makes no difference, because they are completely invisible. The bad books don’t get bought. If they don’t get bought, they don’t get picked up by all those wonderful algorithms that recommend books to readers, they don’t end up in the “also-boughts” listed below the book online, they don’t get reviewed by book bloggers, and they certainly don’t spread through word of mouth. They just sink into the digital void and disappear.

And this idea was completely proven true between 2007 and 2013. Literally millions of manuscripts have been dusted off, digitized, and dumped into the system, and yet not a day went buy for a year or two where the news wasn’t filled with one writer after another after another who was making a killing selling eBooks. This, of course, only encouraged more of the same, and hordes of writers dreaming of easy riches jumped on the bandwagon.

But a tidal wave of bad books was never the real game changer. The real game changer was a tidal wave of good books. This tsunami of wonderful, as I’ve taken to calling it, has been a slow-building process over the past five years. Some of it is the early indie writers getting better: better storytelling, better covers, better blurbs. Some of it is the traditional publishers pouring thousands of backlist titles online, and, over time, getting their average eBook price down to a more acceptable level. Whatever the cause, readers today have an abundance of riches to choose from. It truly is the best time to be a reader.

But a tidal wave of bad books was never the real game changer. The real game changer was a tidal wave of good books. This tsunami of wonderful, as I’ve taken to calling it, has been a slow-building process over the past five years. Some of it is the early indie writers getting better: better storytelling, better covers, better blurbs. Some of it is the traditional publishers pouring thousands of backlist titles online, and, over time, getting their average eBook price down to a more acceptable level. Whatever the cause, readers today have an abundance of riches to choose from. It truly is the best time to be a reader.

Now, do I still believe it’s the best time to be a writer, especially one focused on building an audience and making money (two things which almost always go hand in hand, contrary to what some may think)? Absolutely. All the reasons I mentioned in that blog post three years ago still apply: no gatekeepers, more freedom to write what you want, more control over the process, more profit per book sold. However, there is one important change that’s happening now: While it’s easier than ever for fiction writers to make some money, it’s starting to get harder to make lots of money.

Please note: Harder does not mean impossible. Harder might also mean better, for the dedicated writer with the right mindset. Confused? Read on.

…How the Long Tail of Publishing Is Finally Overwhelming the Early Adopter eBook Bounce…

If you’re not familiar with the concept of the long tail as it applies to book publishing, here’s the most concise definition I can give you: as the cost of production and distribution to readers approaches zero, a vast amount of choices will be  available to readers that weren’t available before, and those expanding choices will mean 1) more books are sold, 2) more consumer money will be spent on books, and 3) that money will eventually be spread out over more titles.

available to readers that weren’t available before, and those expanding choices will mean 1) more books are sold, 2) more consumer money will be spent on books, and 3) that money will eventually be spread out over more titles.

This phenomena hit the music industry about ten years before it hit the book industry (iTunes playing the part of the Kindle in that story), and the effects of it clearly prove the axiom I just stated. For music lovers, this is an incredible time: more choices that cater to niche tastes, easier to get just the songs you want, and every song available at the click of the button. For musicians, it’s never been easier to find an audience and to make some money, and while it’s a given that more money is being spent on music than ever before, it’s also true that those dollars are being spread thinner and thinner across more choices — with a bulk of those dollars still concentrated at the top. Professional musicians, at least those wanting to make a living from their craft, are having to work harder than ever, doing more live shows, selling T-shirts, whatever it takes to bring in enough income streams to pay the mortgage.

Now the same thing is happening to fiction writers.

For a few years, we were insulated from this affect to some degree because there was an early adopter eBook bounce, a huge influx of naked Kindles and Nooks and iPads bought by avid readers who wanted to fill up those devices with as many books as possible. It may be hard to believe, but for a year or two there, demand for good eBooks really did exceed supply. And those writers who jumped in early — the early adopters on the indie publishing side — definitely saw much higher sales per title than they’re likely to see going forward.

I can’t say this definitively. I could be wrong. This is where I’m going out on a bit of a limb, making a prediction based on intuition and only a smattering of anecdotal evidence. But I’ve now heard enough from writers all across the genres that despite working harder and smarter, putting out more titles, getting better, promoting the smart way, they’re seeing a general decline in sales per title, that I can no longer dismiss it. It’s not seasonal. It’s not temporary. Yes, in a business like this one, there’s always going to be exceptions, individual writers bucking the trend but as an aggregate, the long tail affect has finally arrived. The early adopter eBook bounce is over.

For some writers, this has been heartbreaking. More than few have gone from making six figures three years ago to four figures today. And while most new writers would be happy if they were just starting out with the sales figures that these writers are complaining about, it’s the huge decline that’s tough for some of these writers to swallow. Many have added other jobs, teaching on the side, or just given up completely. There have been plenty of traditional writers who quit the past few years because they couldn’t adapt. Now there are plenty of indie writers who are quitting, too.

For many, it was like the irrational exuberance of the stock market in the decade leading up to the September 2008 crash. It was bound to end, everybody knew it, but nobody wanted to believe it would happen any time soon, which was part of the problem.

Depressed? Don’t be. Now I want to tell you why this is still the best time, bar none, to be a writer.

. . . and What This Means for Fiction Writers Going Forward

If you don’t care about making money as a writer, or reaching the widest audience possible, then none of this matters. You still have at your fingertips the ability to reach the possibility of a mass audience at very little cost. Heck, if you have the skill and knowledge, you can currently make a book available in eBook, print-on-demand, and audio for free. Millions of people could buy it. They probably won’t, but they could, and isn’t that exciting? I think so.

But if you’re a professional writer, either full time or part time, one who wants to be compensated fairly for his or her work just like any craftsman, things are going to be different going forward. I’ve long believed that a writer’s success in finding an audience can be reduced to three primary factors: quantity, quality, and luck. Think of it like a pie chart. The bigger one slice of the pie, the smaller other slices must be. If you publish one book in your life, that slice of the pie devoted to luck is awfully large. Chances are, since it’s your first book, it’s not that good, and even if it were good, it’s hard for readers to find you because you’ve only given them one doorway into your work.

But if you’re a professional writer, either full time or part time, one who wants to be compensated fairly for his or her work just like any craftsman, things are going to be different going forward. I’ve long believed that a writer’s success in finding an audience can be reduced to three primary factors: quantity, quality, and luck. Think of it like a pie chart. The bigger one slice of the pie, the smaller other slices must be. If you publish one book in your life, that slice of the pie devoted to luck is awfully large. Chances are, since it’s your first book, it’s not that good, and even if it were good, it’s hard for readers to find you because you’ve only given them one doorway into your work.

What we can do, however, is write more and get better. The more you write, the more ways people can find you, and the better you get, the greater the chance that people will come back for more. And recommend your books to their friends. And join your mailing list. And on and on.

Here’s what’s changed, though. Two years ago, there were plenty of examples of moderately prolific writers with so-so covers and so-so blurbs and so-so writing that were selling pretty darn well. Now? Not so much. The Tsunami of Wonderful is making it pretty hard for what’s so-so to gain any traction with readers. And while right now I’d still say that being extremely prolific is a writer’s best bet and building an audience quickly (there’s a number of writers who have followed this Big Bang approach, writing 8-12 books a year), my hunch is that the long tail will mean the second of the three factors will grow in importance with each passing year.

Quality.

I want to be careful here. I know I’m trying to cross a bridge constructed of tissue paper. It’s highly unlikely that what I consider to be a good book and what you consider a good book are the same thing. In fact, I’d wager good money that they aren’t. What’s considered good is somewhat subjective — but only somewhat. If it were entirely subjective, then there would be no bestsellers, no award winners, no cherished classics that endure year after year. You may hate Shakespeare, but millions of people disagree. You may think To Kill a Mockingbird is a bunch of rubbish, but plenty of people consider it the best American book written.

Quality matters. Quality endures. Quality, consistently delivered, finds an audience. And since we’re all wired with the same basic genetic code, we all tend to agree, in general, on what quality is and gravitate toward it.

“But Scott!” I hear the protests already. “There are lots of bad books that become bestsellers! It happens all the time.”

My first response to that is, are you sure it’s a bad book and just not to your taste? Second, many flawed books contain something else, something special, that more than compensates for other flaws. Third, the plural of anecdote is not data. Luck does play a part. No doubt about it. But if you want to count on luck, spend your hours at the casino playing the slots instead of at the keyboard making up stories.

I ranked the three factors — quantity, quality, and luck — in exactly that order because I believe that’s the order in which you have the most control of each. I still believe a writer needs to be prolific. But being prolific is not enough, especially now.

You need to spend more time improving your craft. When something resonates with you, ask yourself why. How does Elmore Leonard write such snappy dialog that it leaps off the page? Why is Stephen King’s voice so engaging that he could write about an IRS audit and I’d follow along? What is it John Grisham and James Patterson do to make their books so relentlessly readable?

You have to get better.

Now listen, I want to be clear: I’m not saying you should try to construct Great BooksTM by some kind of formula, sit around waiting for the perfect idea to strike, or, even worse, rewrite your books to death. You become a great writer by writing lots and lots of stories, not by rewriting the same story over and over again. Writing is the tool by which we convey stories to readers, but it is only the tool. If you’ve got a rusty hammer, it’s harder to build a house, but the focus still isn’t on the hammer. It’s on the house. Thousands of writers fall down the rabbit whole of focusing on line-by-line writing to the detriment of great storytelling. I happen to love great writing, but what I consider great writing is writing that is fully in the service of telling a great story.

Why do I still think it’s the best time to be a fiction writer? Because, if you embrace indie publishing, you have control. Because there are no gatekeepers. Because you can take risks and nobody can stop you. Because I can sit here in my little office behind the garage, looking at the fall colors decorating the trees outside, and dream up some idea that a few thousand words and a few clicks of a button later can be made available to millions of readers — and might just be bought by them. Because I’m patient. Because I’m not writing to get rich quickly. Because I’m committed to getting better at all aspects of the being a fiction writer, from the craft side to the business side. Because I love great stories and getting better at telling them.

You see, it’s a bit of a trick question. When I say it’s the best time to be a fiction writer, I’m assuming you’re a dedicated writer. I’m assuming you’re in it because you love it, for the long haul, and not just because it’s an easy way to make a buck. And if you are such a writer, that’s really why things are getting better even if they’re getting harder. The early adopter eBook bounce may be over, and it may wash out lots of discouraged writers, but that’s just the point. The gold rush mentality may be past, and most folks may be heading home, but that leaves the rest of us. The ones striving to getting better — at both the craft and the business.

The ones who know the real joy isn’t about finding gold in the hills, but the more enduring satisfaction that comes from doing the work.

——–

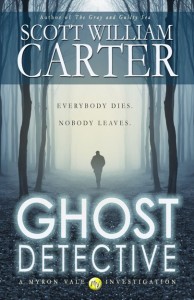

Thanks for taking the time to read this article. If you’d like to show your appreciation, please consider buying my latest contribution to the long tail, Ghost Detective. Shot in the head during what seems like a routine robbery, Portland detective Myron Vale wakes seeing ghosts — all of them. The kicker? He can’t tell the living apart from the dead. You can buy both the ebook and the paperback at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and other retailers

Thanks for taking the time to read this article. If you’d like to show your appreciation, please consider buying my latest contribution to the long tail, Ghost Detective. Shot in the head during what seems like a routine robbery, Portland detective Myron Vale wakes seeing ghosts — all of them. The kicker? He can’t tell the living apart from the dead. You can buy both the ebook and the paperback at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and other retailers