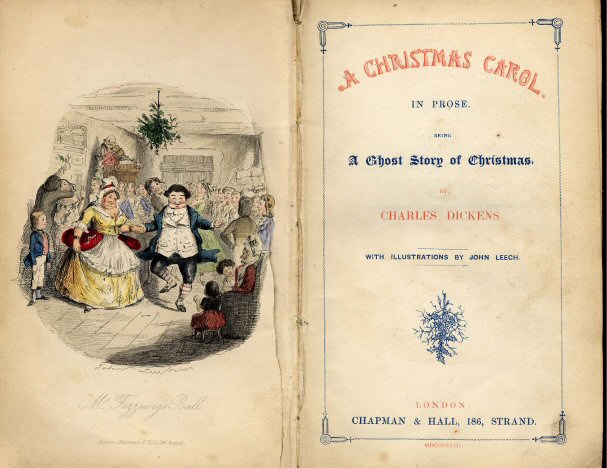

The other day on the way to the day job, I heard a bit on NPR about Charles Dickens and The Christmas Carrol. I knew he’d written it in about six weeks, and that he badly needed money at the time, but I didn’t know no publisher would touch it so he published it himself, that he was nearly bankrupt, and that he was still haunted by the fact that his own father had gone to debtor’s prison. All six thousand copies of the first printing sold out, and the rest, shall we say, is as much a part of history as Tiny Tim’s crutch. That book really turned things around for Dickens — and according to lots of folks, revived the disappearing traditions of Christmas.

The other day on the way to the day job, I heard a bit on NPR about Charles Dickens and The Christmas Carrol. I knew he’d written it in about six weeks, and that he badly needed money at the time, but I didn’t know no publisher would touch it so he published it himself, that he was nearly bankrupt, and that he was still haunted by the fact that his own father had gone to debtor’s prison. All six thousand copies of the first printing sold out, and the rest, shall we say, is as much a part of history as Tiny Tim’s crutch. That book really turned things around for Dickens — and according to lots of folks, revived the disappearing traditions of Christmas.

This story really resonates with me because it touches on many of the things I’ve been thinking about lately when it comes to writing. The first is the value of hunger to a professional writer. What I mean is, knowing that if you don’t write, and that if you don’t get your work out there if front of people who can pay you money for it, you might actually starve can be tremendously motivating. Of course, there are other writers who lock up in such a situation, and still others who get ground down by such pressure and eventually quit the business. It cuts both ways — it can be motivating, but it can take all the joy out of writing. And the joy feeds another kind of hunger, which I’ll get to in a moment.

I think achieving success as a writer depends largely on figuring out which kind of writer you are, but it can also depend a lot on your life choices. I tend to like pressure situations. When I was 24, I quit a good job and started a used bookstore with practically no savings. I made zero the first year, peanuts the second year, and slightly more peanuts the third year. I understand burnout, because by that third year the joy had gone out of being a bookseller, and I knew I needed to sell the business to someone with new energy before my souring attitude hurt the business. Which I did, for a profit. And I happily went back to having a regular day job. I recognized the signs and got out quickly before it took too much of a toll on me or the business.

So I completely understand writers who get ground down by the pressure of it all, whose souring attitudes kill the original passion they had for writing in the first place. Me, I’d apply the same approach to writing in a heartbeat that I applied to the bookstore (do you know how much easier it would be to make a profit when you don’t have to pay for 2000 square feet of prime retail space?), but circumstances have changed in my life. It was one thing to take my wife along for the ride when I gave up the regular paycheck (although that was stressful enough, believe me, especially when she was between jobs at one point), but taking two children under the age of 6 along for the ride is a whole other matter. Stress is one thing. Guilt is a different animal. I don’t handle guilt so well, and honestly, I don’t want to be the kind of person who does.

When I look at the writers I know who have achieved a lot of success with writing, they fall into two camps when it comes to day jobs. The first are the ones who made sure writing was the very center of their lives and often got trivial, brain-dead jobs, usually part-time, that allowed them to focus as much as possible on their craft. They often hopped on and off a day job, were dirt poor much of the time, especially in the early years, but they used the threat of poverty and even homelessness to motivate them. They were writers, damn it, and they were going to keep on being writers no matter what.

The second type are the people who get careers outside of their writing, frequently get married, have children, and all in all, end up very settled. They often have the typical middle class life with the house and the two cars and the frequent dinners out at Applebees. These writers fitwriting into their lives, rather than their lives fitting into their writing (as in the first camp). Now, remember, we’re talking about the writers who have made it — being roughly defined here as writers who support themselves solely by their writing. There are lots and lots of writers who have made it who fall into this second group — Stephen King, Nora Roberts, John Grisham, just to name three big ones right off the top of my head, let alone the thousand of mid-listers whose names even hardcore readers wouldn’t recognize. It’s a lot more common than writers in the first group. But the danger with this second approach to the serious writer is that you may lose the first thing I wrote about above — hunger.

You get comfortable. It’s a little too easy to put off writing, to get distracted by a life full of distractions. You’ve worked hard, after all. Don’t you deserve to sit in front of the tube for an hour with a beer watching that Celtics game? Sure, you do. But then, you know, an hour turns into two, and then it’s time to shuffle off to bed and start over again the next day. There goes a life.

If you go with this approach, and your desire is to eventually leave your day job, you’ve got to get hungry some other way. You have to remember that no matter what your business card says, you’re first, second, and third a writer. It’s hard. It’s easy to start to feel the subtle clinch of those golden handcuffs being fastened around your wrists. Believe me, I know. I’ve been self-employed, so I can tell difference. Benefits are nice. So is a pension plan. Paid holidays, vacation, sick leave, a comfortable office, the list goes on.

But here’s what’s really interesting. I am very much a goal-directed person, but when I look at my goals now, the words “become a full-time writer” are not even listed. That actually surprised me. And yet, I have every expectation that eventually I will be supported solely by my writing.

Contradiction? Nope. Let’s say you have a goal of being a bestselling fiction writer. For me, becoming a full-time writer is most likely a bi-product of that goal. What I mean is that at the point your day job becomes a hindrance rather than a help to you, then you’ll leave it behind — either by getting a different day job, or, if you no longer need one, going without it. That where’s I fall. I have a great day job. As long as I stay on track with my writing, I’ll stick with it. If it becomes a hindrance at any point along the path, then I’ll get rid of it — either by getting a different day job, or by getting rid of the day job altogether, if I feel it benefits me more to go without one.

There are many, many aspiring writers who buy into the false panacea that if they only didn’t have a day job, they’d write so much more. Nonsense. The vast majority of writers who leave their day jobs, even the most successful, hardly ever write more than they were writing before. It’s just damn hard to write more than two or three hours a day, day after day, even twenty days a month. Short spurts, sure, but the writer who can crank fiction even four hours a day, week after week, is a rarity. And usually, when they claim they do this, they take long breaks in between projects, which just averages out to the same thing.

No, the real reason to become a full-time writer is because you want time for everything else — reading, research, movies, time with your family, nights out with friends, you name it. When you have a day job, and you’re serious about writing, you sacrifice many of these things to work on your craft.

So let’s say you’re an aspiring professional fiction writer. I assume, like me, you’re in this for the long haul. The first thing you have to decide is whether you fall into first group or the second. Then, if you’re comfortable being in that first group, if you’d relish the stress that comes with that gnawing feeling in your stomach that says you haven’t eaten that day, if you find that motivating, then next you have to decide if you’re comfortable imposing that uncertainty on everyone else in your life (if it’s just you, then it’s a short conversation). If not, then you put yourself in the second camp, too, but you do it fully recognizing that you have to find that hunger in yourself to stay on pace, to work as hard as your soup-eating, bus-riding counterparts.

There’s perils to both approaches. One is physical starvation. The other is starvation of the soul. In my opinion, it’s even more deadly than the physical kind, but it can motivate you just as well when you pay attention to it. You don’t want to be walking this Earth but be dead inside. That ain’t no fun. I didn’t sign up to become a zombie.

Of course, both approaches can lead to burnout. How do you avoid that? By fiercely protecting your passion for the craft. You got no passion for the craft? You don’t feel those butterflies in the stomach when you get the urge to write something new? You don’t feel the thrill of reading another writer who makes you want to write something just as good? Then give it up now. Seriously.

Or if you’ve lost it, make some changes quickly to get it back. That’s the fire that keeps you going through those hard days. It’s the fire that you huddle around when night falls and the storm blows into the valley. You don’t got the fire, you don’t survive those storms. Cherish the fire. Protect the fire. I write because I love stories, both reading them and writing them, and I want to get better at the latter. As long as I protect those feelings — the thrill of creation, the joy of learning — then there isn’t anything about this business that could ever get me to quit.

Because, you see, I’d self-publish if I had to. I’d even sell badly photocopied, stapled books out of the trunk of my car if it came to it. I’d rather not. I’d rather a good publisher did that work for me, because, honestly, a good publisher is going to be much better at getting my work out in front readers than I would ever be. But I’m hungry, you see. I’m hungry to tell stories, and I’m not going to let anyone take away that hunger — reviewers, publishers, even readers if it comes to it. (Although if I don’t have any readers, then I’m not really a storyteller in my book, which is a whole other problem). It may not be a physical hunger, but it’s the best kind. In the end, it’s the kind of hunger writers in both camps have to have. You lose that hunger, that love of storytelling, the joy of getting better at it, then it’s just a job to you, and there are much easier jobs out there.

Charles Dickens may have felt actual physical pangs of hunger, but he had the other kind of hunger, too. He wanted to write a damn good tale, have a lot of people read it, and put bread on the table for his family. He was having fun. He felt the love of the craft. And millions of people around the world — everyone who’s ever read A Christmas Carrol or seen a play or movie version of it — have benefited from his hunger. So if you’re an aspiring professional writer, whatever approach you take to your writing, stay hungry. The right kind of hunger.

You know exactly what I mean.