Chapter 1

They walked side by side, but alone. The beach was deserted, the sun a soft yellow glow behind a vaporous orange film along the horizon. It had been the first day without rain in weeks, overcast and breezy but no rain, the big storm of mid-March already receding into memory.

Gage, carefully navigating the driftwood with his cane as they made their way to the smoother sand near the water’s edge, stole a glance at Zoe. Her wool hat was pulled low enough that he could barely see her eyes. Even on a Wednesday in April—not exactly the height of tourist season in Barnacle Bluffs, Oregon—having the beach to themselves was enough of a rarity that one of them should have commented on it, but neither of them did.

He still didn’t know how to overcome the hard thing between them. He didn’t know what it was. When they actually managed to talk, they argued. When they didn’t talk, it seemed uneasy. Uneasy was better than arguing, so most of the time they opted for silence.

“I’ve got something for you,” she finally said.

She sounded timid, her voice disappearing into the crashing surf. It wasn’t like her. She went on staring at the ocean and for a moment, in the soft, drowsy light of dusk, he clearly saw the woman she was becoming and not the girl she’d been. All the hard edges of her troubled youth were beginning to fade. Where was the facial jewelry? Where was the spiky black hair? Now she didn’t even sport the tiny nose stud she’d been wearing the past few months, and the auburn hair sticking out of the hat had grown long enough that it actually billowed in the wind.

“Oh?” he said.

“I’m not sure you’re going to like it,” she said.

“Uh oh.”

“Actually, I’m pretty sure you’re not going to like it. Promise me you’ll keep an open mind.”

“This conversation is already not starting well.”

“Just promise.”

“I’m always open-minded,” he said. “You know that. That’s why they call me Garrison ‘Open-Minded’ Gage.”

He’d been hoping for a smile, but he got a sigh instead. Overhead, through fragmented clouds dappled with bright crimsons and sober violets, glimpses of a more cheery blue could still be seen. To the right, where the beach stretched for miles, the lights of the Golden Eagle Casino far in the distance blinked through the pink haze. To the left, where the bluffs grew taller and the houses more impressive the higher they were, the view ended a few hundred yards away, where the bluff jutted out to some exposed black rocks. Zoe went left. When the tide was low, which it was now, there was a gap in the rocks that allowed passage without requiring them to wade into the surf, but Gage still usually went right. His bad knee—far too bad a knee for a man who could still believably claim to be middle-aged—made him wary of hidden dangers.

The salty air, abrasive yet still somehow welcoming, cleared the dust from his mind, shook off his evening bourbon. He followed Zoe to the rocks, watching her back, wondering what this was all about. Everybody told him that when she became an adult, it would get easier. She was eighteen now. How long did he have to wait?

She hadn’t gone far when she turned and thrust something at him. It was shiny and black, small enough to be cupped completely in her hand.

“Here,” she said.

“What is it?” he asked.

She flipped it open, turning the tiny blue-glowing screen so it faced him. A cell phone. He felt a sinking disappointment.

“Ah,” he said

“Take it,” she said.

“And here I thought you just wanted to walk with me.”

“I did! I just, I had this for you, too.”

“Zoe …”

“Come on, Garrison. You can’t go through life without a phone anymore.”

“I have a phone.”

Her hat had inched up far enough on her forehead that he could see her eyebrows raising. Like the rest of her, they had also undergone something of a change, plucked and trimmed to perfection. At some point Goth Girl had decided to become Model Girl. He didn’t know why. It seemed to be the opposite of everything she claimed to believe in—nonconformity, individual expression, indifference to other people’s opinions.

“I use the pay phone at the gas station down the hill,” he explained.

She smirked. “Right. Funny how that’s like one of the only pay phones left in Barnacle Bluffs.”

“It’s a convenient coincidence.”

“Or,” she said, “it could be because you agreed to pay the owner the monthly bill just so he’d keep it.”

“Who told you that?”

“The owner,” she said.

“Ah.”

“I just don’t get it. If you’re willing to go that far just to have access to a phone, why don’t you just get a cell phone?”

“Call me a conscientious objector.”

“I can think of many other words for you.”

“Most of those probably apply, too. Look, I appreciate the sentiment—”

“Just take the damn phone,” she said.

“Zoe—

“Take it!”

Her fiery tone shocked him. He took it. What else could he do? It felt like cheap plastic, inconsequential, hardly worthy of so much drama. She glared at him, squinting at him in the wind with dark eyes, then turned in a huff and marched toward the rocks. He stuffed the cell phone into the pocket of his leather jacket and followed, holding his cane in his effort to keep up. His throbbing right knee threatened to buckle. It never did buckle, though. Somehow, if he could endure the pain, it always seemed to hold. If there was one thing he had proved in his life, even if he had proved nothing else, he could endure a lot of pain.

“Zoe,” he said, “what’s all this about?”

She hustled for the gap in the rocks. He wondered if this had something to do with her living at the Turret House the past two weeks. His good friend Alex had taken his wife on a long-deserved vacation cruise to the Mediterranean, where they were also visiting some of her relatives in Greece, and Zoe had been staying at the bed and breakfast until they’d returned yesterday. He didn’t know why that would make a difference. Since becoming Alex’s full-time assistant, she practically lived there most of the time anyway, a fact that annoyed him to no end. She should have been back in school by now.

He caught up with her as she reached the gap, a damp breeze swirling through the shiny black rocks. The air smelled of kelp and dank earth. He reached for her arm, but before he touched her she inhaled sharply.

He thought it might have been because of him until he looked over her shoulder and saw what she saw.

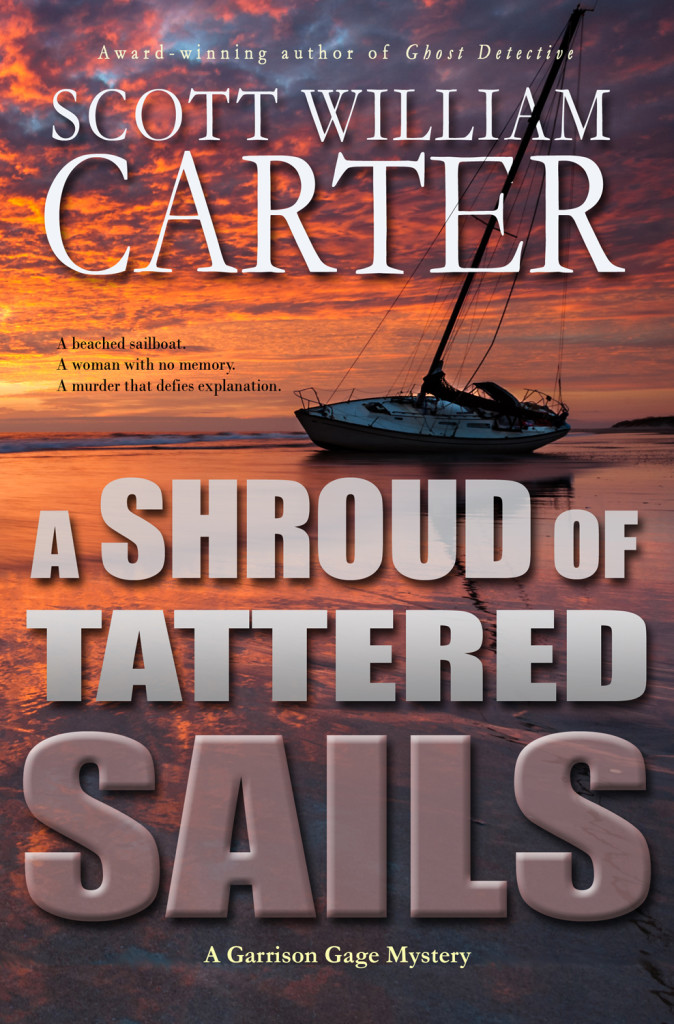

A sailboat, a 30- or 40- footer by the looks of it, was beached a hundred yards from them. Tilted away from the surf that lapped at the white fiberglass hull, the mast a stark black line against the sunset and the wet sand a mirror reflecting all those rich amber and violet hues, the boat looked at first glance like something out of a photographer’s dream—as if someone had arranged it just so to get the perfect shot. It was only when Gage stared at it a little longer that he noticed how shredded both the main and jib sails were bunched at the base of the mast. Not much remained of them.

Barnacle Bluffs had no ports. A sailor could find refuge in Newport to the south or Tillamook to the north, as well as a number of other seaside towns that truly catered to the fishing trade, but this part of the Oregon coastline was inhospitable to anything bigger than a kayak. Too many rocks lurked just below the water’s surface. Gage assumed the sailboat had been abandoned, washed ashore after weeks or months adrift, the owners rescued by someone who did not have the means to take the broken boat in tow. This had happened before. The ship would be a curiosity for a few days, worthy of an article or two in the weekly Bugle, then someone would haul it away and it would be forgotten.

That’s what he thought until he saw the woman emerge from the hatch.

From this distance, with the sunset at her back, she was hardly more than a silhouette—tall, stick-figure thin, dressed in a bikini top and tiny shorts, clothes not at all fitting for the cool weather. Her frizzy hair, lots of it, formed a halo around her head. She staggered to the stern, teetered, then swung one unsteady leg over the metal rail. Both Gage and Zoe started for her, hurrying but not running, until the woman slipped and fell.

Then they ran.

The woman lay face down in the water. Zoe reached her first, splashing into the foamy surf, with Gage not far behind. He’d dropped his cane, enduring the excruciating throbbing in his knee to keep pace. Icy water soaked his tennis shoes. Zoe grabbed the woman’s shoulder, turning her, and Gage seized the woman under the arms and pulled her out of the water onto the sand. She felt as light as a mannequin.

Already, she was coughing and hacking up salt water, a good sign.

They knelt beside her. The coughing didn’t last long, then the woman rolled onto her back, gasping, eyes closed. That mass of reddish brown hair was as thick as dreadlocks, dark and wet around the temples, her face shiny from her dip in the ocean. Her bikini top and shorts, which might have once been yellow with white polka dots, were bleached white with faint patches of yellow. Her skin was a golden bronze in some places, but reddish pink in most of the others, the way someone with pale, freckled skin usually tanned. Judging by the hint of crow’s feet around her eyes, he guessed she was in her early 30s.

There really was nothing to her. She made Gage think of those runway models with the physiques that only appealed to the fashion industry—gaunt faces and gaunt bodies, shoulder blades that could have been sharpened like knives. But she was pretty, definitely pretty, with the face of a small-town girl who’d gone to New York or Los Angeles and somehow, even as she lost herself, never lost the look of herself, that wholesome Midwestern appeal, before the years passed and the big city turned to younger, more pliant versions that always seemed to be in endless supply.

Gage felt ashamed of himself when he realized he was projecting all of these assumptions onto this poor waif of a woman—a woman who was only now opening her eyes. Green eyes. Aquamarine. A fitting color for a woman from the sea. Janet had eyes that very same color. And what made him think of that? Strange. The woman blinked a few times, staring at the sky, seemingly unaware of Gage or Zoe. He expected to see relief there, or at least some panicked confusion, but there was nothing. She simply stared at the sky.

She did not seem like a woman who’d just climbed out of a beached sailboat. She seemed like a woman who’d decided to lie down for a nap after having one too many margaritas.

“Who are you?” Gage asked.

She peered at him for a long time, blinking slowly, looked at Zoe, then back at Gage. Her cracked lips parted as if she was about to answer, but all that came out was a long, quiet moan. It was only then that a bit of fear crept into her eyes.

“I don’t know,” she said.

Her voice had the rough quality of someone who hadn’t used it in a long time. Gage saw her fear growing, blooming into panic. He figured it was just the shock, that she’d come back to herself in a minute.

“You don’t know?” he said.

She shook her head.

“Your name?” he pressed.

“No.” The terror was palpable now. Even though her voice was soft, he heard the hysteria emerging. “No … Oh, God. Oh God, no.”

“Do you remember the boat? It looks like you really had a rough ride. Do you remember that?”

She rolled her head to the side and gazed at the sailboat as if she not only didn’t remember it, she didn’t even know what it was. Then, abruptly, she burst into tears. Gage realized he was being an idiot. She was in shock, probably dehydrated. This was no time for twenty questions. He looked at Zoe and she must have been thinking the same thing.

“Use your phone,” she said.

It took a second for him to even remember what she was talking about, then he reached into his pocket. It wasn’t there. He searched all of his pockets. It wasn’t in any of them. He scanned the area around them, and then, when he happened to glance in the direction of the boat, spotted something black and shiny in the shallow water. When the wave retreated, leaving the object caked in sand and sea foam, he saw that it was the cell phone. Zoe saw it too.

“You’ve got to be kidding,” she said.

* * *

Using her own phone, Zoe called 911. Gage heard the sirens within two minutes, growing louder on the bluffs, and within five minutes two male paramedics charged over the sand with a stretcher between them. By then, the woman had stopped crying. While they checked her vitals, she gaped at them like a rabbit caught in a snare. A state trooper arrived a moment later, a young muscle-bound guy Gage didn’t recognize, peppering her with questions like bullets from an automatic rifle. What was her name? What happened on the boat? Who should they call? She didn’t answer and Gage told the kid to back off a little, give the woman some time. The paramedics loaded her onto the stretcher and started to haul her away.

“No, no, no!” she cried. She flailed aimlessly about and caught hold of the sleeve of Zoe’s windbreaker. Her eyes flew wide open and a vein on her temple pulsed violently. “Please! Don’t—don’t let them … He’ll find me!”

“Who?” Gage said.

If she had been any stronger, the panic would have prompted her to break into a run, but as it was she only had enough energy to lift her head. It was a shuddery, jerky motion that she only managed to maintain for a few seconds before she collapsed on the stretcher—and then she was again crying inconsolably, unresponsive to any of their soothing words. The paramedics started for the stairs, but the woman refused to let go of Zoe’s sleeve.

Gage reached to pry her fingers free, but Zoe shook her head.

“I’ll go with her,” she said.

“You sure?”

“She needs someone.”

“Okay. I’ll follow in the van.”

Gage watched the woman get hauled away, Zoe walking by her side like a dutiful pallbearer. The sun had slipped completely beneath the waves by this point, robbing the sky of all the yellow and turning the blues to violets and the violets to blacks. The state trooper asked Gage a bunch of questions about the woman and the boat, none of which Gage could answer. Two other local cops showed up, a man and a woman, as did Percy Quinn, the sober-faced chief of police.

“What did you do now?” Quinn asked.

The chief, who usually dressed like an undertaker after a long day, in frumpy white dress shirts and thin wrinkled ties, had tossed his gray trench coat over a ratty blue t-shirt, a packet of cigarettes bulging in the shirt’s front pocket. Grease stained his hands and he had a bruise on his forehead almost as dark as his thick eyebrows. His wispy gray hair batted about in the wind.

“Went for a walk,” Gage explained.

“Well, you should stop doing that. It always seems to lead to something bad.”

“Like talking to you?”

Quinn had his own special brand of smirk he seemed to reserve only for Gage, one heavy with both impatience and burden, and he employed it now. The state trooper who’d been first on the scene caught the chief up with what they knew, which wasn’t much, then the whole bunch of them descended on the boat. Charity Case was written on the side in stylish black script. Unusual name. Gage wondered about the meaning behind it. Quinn pointed to the license number on the side and asked one of his cops to call it in and get the registration info.

While he was talking, Quinn noticed the cell phone in the water. He picked it up.

“That’s mine,” Gage said.

Quinn raised those expressive eyebrows. “You have a phone?”

“Zoe got it for me.”

“And, what, out of spite you tossed it in the ocean?”

“I dropped it in the ocean. On accident.”

“Maybe you were being passive aggressive. On accident.”

Quinn, clearly suppressing a grin, opened the phone, found it dead, and handed it to Gage with a shrug. Gage shoved the stupid thing into his jacket pocket. Meanwhile, the female cop climbed onto the boat on the starboard side and, using the rail for support, made her way to the stern. Her partner, another young male cop, joined her, and the two of them ducked into the cabin. Gage, Quinn, and the state trooper first on the scene waited and watched what remained of the sails flutter in the quickening breeze. Up close, Gage saw how thick the algae was on the hulls, how weathered and beaten the wood trim. He wondered if it was the big storm a couple weeks earlier that had crippled the ship.

The state trooper on the phone clicked off and stepped over to Quinn. “It’s registered to a Marcus Koura out of San Jose, California.”

“Reported missing?” Quinn asked.

“No, sir,” the cop said.

“Hmm. I wonder where Mr. Koura is now.”

“I have no idea, sir,” the cop said.

“It was a rhetorical question, son,” Quinn said.

It may have been rhetorical, but Gage could see where Quinn was going with the line of thought, and it made him uneasy. That he felt uneasy made Gage even more uneasy. He could already see that he was rooting for this woman, that he had some kind of blind spot forming, and he didn’t like that at all. When the young male cop poked his head out of the cabin, Gage tensed. He was tall, dark-haired, and athletic, the perfect mold for a police officer, but with a baby-faced innocence that didn’t fit—the kind that only reflected back what was good and decent in the world, like a mirror that only revealed your best features and hid the rest. Naturally, Gage feared the worst.

“Nobody else in here,” the cop said.

“Men’s clothes?” Quinn asked.

He ducked back inside. He returned a few minutes later with the female cop, both of them shaking their heads.

“No clothes at all,” the male cop said.

“None?”

“No, sir. Not unless they’re stowed somewhere else. I can’t find a bag or anything. No food or water or anything either. Not even wrappers and stuff. Weird.”

“Weird indeed,” Quinn said. He looked at Gage. “Woman shows up in a man’s boat, but man isn’t in it. She claims to have no memory, but she yells out that someone is after her. What’s your brilliant deduction, Mr. Detective?”

“Don’t have one,” Gage said.

“Really? I figured you’d have it solved by now, being the famous private investigator that you are.”

When the male cop on the boat started back inside, Gage spoke up. “You know, you guys might want to hold off on that. Maybe you should think about getting a warrant first.”

The cop stopped and looked at the chief questioningly, who, in turn, looked at Gage with a similar expression.

“Really?” Quinn said. “You’re going to play this one that way? For a woman you don’t even know?”

“You’ve already determined that there is no one else on the ship,” Gage said. “Do you really have enough probable cause to think foul play is involved? I’m just looking out for you here.”

“How thoughtful,” Quinn said.

“Sir?” the cop on the boat said, still poised at the hatch. “You want me to keep looking or not?”

Quinn’s scowl appeared to deepen, but it may have just been the fading light, the shadows accentuating all the many grooves on his face. Behind him, the boat was losing its detail, becoming a solid black silhouette, the sky and the ocean merging together in the gloom. The breeze had died, the air still enough that he smelled the pungent kelp at their feet, quiet enough that he heard the excited murmur of the onlookers on the bluff. Gage didn’t glance at them. He kept looking at Quinn instead, waiting for his response to the cop’s question.

Finally it came, a slight shake of the head. The cops took it as an answer, climbing down from the boat, but Gage could see that the real shake of the head was aimed at him.

“There could be a logical explanation,” Gage said.

“Let’s hope,” Quinn said.